4th Year Russian, 3rd time around

I was 15 when the Cyrillic alphabet shifted from an exotic set of vaguely-familiar symbols to something I could read. After attending high school in Argentina for a summer as an exchange student (where I was first introduced to Harry Potter and his “piedra filosofal”), I had run out of Spanish classes at my high school. But I was a language person, and the brightly-colored closet doors lining the side of the language teacher’s classroom, covered in unreadable text with some connection to this thing called “cases” called to me.

I learned Cyrillic in an afternoon and immediately wanted to do things with it, but I didn’t know any Russian. Instead, I practiced the lines and loops of Cyrillic cursive by rambling on in transliterated Spanish. That wasn’t enough: I wanted to be able to type in this new alphabet, and not rely on pen and paper. I enabled the Russian keyboard on my Windows 2000 laptop, hit each key in turn to see what it produced, and then labeled it with an impossibly tiny piece of paper and Scotch tape.

The grammatical structure of the language left me gushing to my friends with excitement. Still haunted by the Spanish preterite, I was thrilled that there was only one past tense form — even though you have to learn [at least] two verbs for every verb: a perfective and an imperfective form. The first words I learned were scaffolded with mnemonics. Most of them have been absorbed back into my brain as their utility faded, but I remember being terribly pleased with myself for coming up with “Mr. Magoo (могу ‘I can’) can(n’t) see.”

Russian was my way out. I lived in a different city from the rest of my classmates and couldn’t drive — not that a license would address the lack of a car. I lived in terror of a real-life wicked stepmother and step-siblings, and I threw everything into learning Russian, getting up at 5:30 AM for extra studying time, because knowing Russian was something they couldn’t take away from me. In one school year, I went from not being able to read Cyrillic to winning the Washington state high school Olympiada of Spoken Russian, and with it, a trip to Russia to compete in the International Olympiada. Relatively recently-elected president Vladimir Putin’s wife gave the opening remarks at the event, though the American team missed it due to flight delays.

All of my suitcases came home from that trip filled to the airline weight limit with books and CDs. I bought all the Nautilus Pompilius albums I found in a small CD shop. I wasn’t big on Napster in high school, and even if I were, I wouldn’t have known what to search for. Nautilus Pompilius was an anchor for me in the world of Russian music, and even as the more complex syntax and vocabulary eluded me, I’d whisper along with the words and phrases I knew. “Слушая наше дыхание, я слушаю наше дыхание…” (“Listening to our breath, I listen to our breath…”) I listened to those CDs over and over, turning the Discman volume as high as I could without getting yelled at, and imagining that the Montana snow when I visited my step-grandparents was the snow of Siberia.

I won the regional Olympiada again the following year, this time securing a scholarship to the University of Washington’s summer Russian program. Another way out: I could spend the months before leaving for the University of Chicago in Seattle, on my own. This was 4th Year Russian #1: a summer in the classroom of Zoya Mikhailovna, my high school Russian teachers’ own Russian teacher. Time had mellowed the fearsome persona they had recounted to me; she no longer perched on the edge of the desk in a short, tight dress, smoking cigarettes. She was grandmotherly. She insisted that there’s no such thing as громкая музыка ‘loud music’, one just plays music loudly. (I disagreed then, and still do now.) I loved the playfulness of the lyrics of “Привет” (“Hello”), one of many texts we read and listened to that summer. A roommate situation had gone badly in the Russian House, so I spent that summer keeping to myself outside of class, passing the time wandering through Seattle or sitting in my anonymous dorm room, chatting on AOL Instant Messenger mostly in transliterated Russian with Andy, who I had met on the UChicago message boards for incoming students. He had also taken Russian in high school, and was similarly interested in languages and linguistics. (Reader, I married him.)

I went to Chicago ready to leave Russian behind me, the life raft that helped me survive a tempest no longer needed. I was an independent adult, and the path I would choose would be Japanese, a language I’d loved since childhood. I had managed to find a copy of the obscure textbook used by UChicago’s Japanese program (in those early days of e-commerce), and using that as a self-taught crash-course, I bluffed my way into second-year Japanese, promising that I’d remedy the deficiencies in my kanji vocabulary.

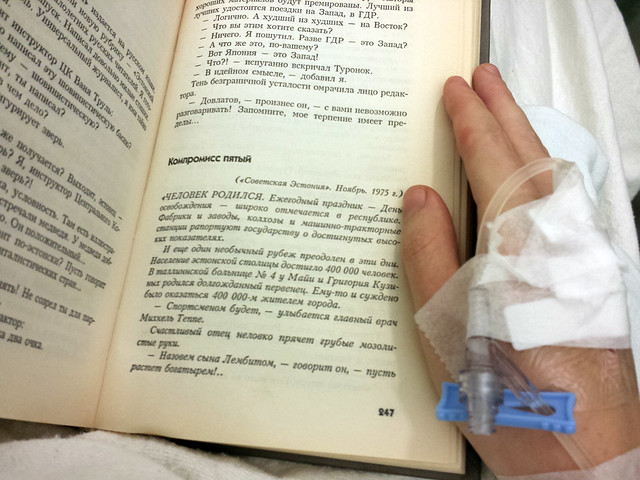

Jumping into second-year Japanese taught me the limit of my language-learning abilities. By my second quarter of college, I had dropped the language altogether, too proud to be downgraded to first-year. Instead, I took a Russian placement test, and placed into “any level you like”. Short stories sounded better than movies as a medium for language-learning, which brought me to 4th Year Russian #2: modern Russian literature with Radik. He was a grad student then, though as a first-year undergrad I had very little sense of what that meant in terms of institutional hierarchies or power. He was just Radik, and he was warm, wonderful, welcoming, and endlessly patient with a classmate who appeared to deploy the instrumental case completely at random. In that class, Andy and I wrote essays and stories — I wrote one, in the spirit of Velveteen Rabbit, about a college dorm room bed in possession of a soul, watching students come and go as time passed. We read Akunin and Dovlatov, among others. Dovlatov's “Компромисс 5” (“The 5th Compromise”, available in English only in a bad translation) stayed with me. Nearly 10 years later, it was the story I brought with me to read at the hospital while waiting for the anesthesiologist, before a procedure to clean out a missed miscarriage.

After 4th year Russian came 5th year, and movies like Брат (“Brother”) and Брат-2 and their soundtracks. In Брат the protagonist wanders around listening to Nautilus Pompilius on headphones, bringing me back to my high school days. We named the first cat we got in college after Vitya, the brother in those films. Andy had a well-curated collection of Russian rock mp3’s, and I eventually adopted his tastes as my own with help from an external hard drive. Highlights from the DDT discography permeated those years; Andy printed out lyrics and guitar tabs and we’d drink and sing. Sometimes I didn’t know the lyrics, and sometimes I didn’t understand them (it took me the longest time to realize метель, “metel’", snowstorm, was not a cognate), but the songs of ДДТ, Сплин, Аквариум, Земфира, Би-2, and others became familiar and comforting strings of syllables set to music and punctuated with meaning.

I decided I wanted to make films, not go to college, so I needed something easy to major in. Russian did the job: most of the degree was taking Russian, and I’d tested out of it. Then I decided I wanted to go to grad school and become Dr. Quinn, just like my childhood idol, so I got a BA/MA program created in the UChicago Slavic department. I was the first to graduate with the degree in four years, due to good fortune in the relative alphabetical ordering of my surname vs. Andy’s. That fall, we both started (though it felt like “resumed") the PhD program in Slavic linguistics. And within a month, I decided that I was more interested in helping people do their research better than actually doing research. I decided to leave the Slavic PhD program.

Time passed. Andy and I got married, with wedding rings inscribed with the text of perhaps the first Slavic gay love letter, in the original handwriting. I started working in UChicago’s central IT organization, and was pulled into the now-infamous digital humanities cyberinfrastructure initiative Project Bamboo. More than once I made gestures towards improving, or at least maintaining, my Russian. On one long road trip, we made CDs of an audiobook of Ночной дозор (Night Watch) and I followed along in an ebook. But speaking was never my strongest skill, and silence was the most reliable way to avoid embarrassment.

More time passed. We moved to California, and all the sunshine and flowers and laid-back attitudes proved to be a fast track to alienation from Russian. Russian rock fell off of my playlists for daily listening. Soon, I was a parent — and I discovered the world of difference between hypothetically wanting to teach one’s future children a language, and actually teaching the unique person who is your child a language, especially when you have no connection to a community or relatives who speak it, to say nothing of the opportunity or means to travel to a country where it’s spoken. There was one beautiful year where our pre-verbal toddler loved Маша и медведь (Masha and the Bear), available in Russian and a host of other non-English languages on YouTube. But then Netflix released an English dub, the toddler learned the words to express other interests, and the fun was over.

Still more time passed. An aunt’s health crisis while visiting over the holidays marked a brief return of Russian to my playlists. Russian settled in like the Bay Area’s summer fog to accompany the self-perpetuating rot of organizational dysfunction at work. Even with Spotify at my fingertips, the same familiar songs provided the soundtrack to my gloom. Russian became an ossified ritual for enacting my unhappiness. Salikoko Mufwene, a linguist at UChicago who once generously humored me as a prospective college student, and served on Andy’s dissertation committee a decade later, has written extensively on language death. From “A cost-and-benefit approach to language death”: “In a nutshell, languages die, gradually, as speakers practice them less and less, because they have fewer and fewer opportunities to use them, basically in the same way people forget to adequately use technology that they have not often had the need for… One may argue that a language is not only a communicative system used by a particular population but also the reality of practicing it. It lives in the practices of its speakers, not in the knowledge people have of it.” Last summer, as I faced at least a year of perpetual exhaustion with a 4-year-old, 2-year-old, and newborn, I came to peace with idea that Russia was something I needed to leave behind me. Knowing and using Russian needed to join defragging hard drives as something I used to be able to do.

But then, to draw on another Mufwene analogy, there was a radical shift in my own linguistic ecology. Unexpectedly taking a job at Stanford to be the Academic Technology Specialist for the Division of Literatures, Cultures, and Languages (which includes a Slavic department) meant that Russian suddenly had value beyond being a go-to “fun fact about yourself” in corporatist ice breakers. In my time at UChicago’s Slavic department, there was a sort of “gentleman’s agreement” among the faculty and students, where we all agreed that we all could speak Russian, so there was really no need to ever do so once you’d passed 5th year. The classes were all in English, the guest lectures were all in English, and it was generally advisable to conduct one’s affairs in English, lest it come to light that your Russian (or your accent) wasn’t actually what it should be. A few weeks after starting my new job, it was a shock to attend the fall tea for Stanford’s Slavic department and find grad students comfortably speaking Russian with one another, the lecturers, and the professors, while I sat mutely, awkwardly, angry with myself for inevitably being the cause of a conversational switch to English.

A few weeks ago, DDT came to Berkeley. Andy and I found a babysitter, and went to the concert along with two good friends. Standing in line, we were the only English speakers in earshot, which had the upside of serving as linguistic anti-spam: the promoters of other Russian bands would just skip over us when handing out flyers. The concert was amazing — a sold-out crowd singing along to classic favorites, dancing along to the newer songs we all knew less well, dudes giving each other spontaneous bear hugs once the alcohol kicked in, real lighters — not just raised cell phones— swaying along with the music (because of course there’s Russians who still smoke despite the intense social opprobrium in the Bay Area), and shout-outs to engineers and people from various former Soviet republics, called out individually. “And there’s Americans here, too. Good for you for coming.” Between the DDT concert and working with Russian materials for the non-English digital humanities course I taught last quarter, I got a reminder that not all was lost. I can still follow spoken Russian, mostly. And I can still read, slowly and with dictionary support. But when a serendipitous introduction to one of the Russian lecturers led to an invitation to audit 4th year Russian this quarter, I had to say yes.

Today I found myself walking into 4th Year Russian #3 with Rima, and one undergraduate international relations major. The class is conducted entirely in Russian. We conversed for much of the hour, read aloud from a text where stress was marked on words (which irked me — only beginning or intermediate textbooks are written with marked stress — even as I was grateful for the marks in moments of hesitation), and did a “choose between perfective and imperfective verbs” exercise. After 20 minutes, my brain was starting to hurt. After an hour, I found that even my English was failing me in the meeting that followed. I have a lot of homework for Thursday, and was promised even more homework for next Tuesday “since you have more time on the weekends.” “I have LESS time on the weekends, I have three kids!” I protested — as I tried to remember whether the number 3 triggers genitive singular or plural. Enumeration is hard.

This isn’t about digital humanities (for a change), but what I’ve learned there applies here. To be perfectly honest, I suspect I would have been fighting back tears if the first day of 4th Year Russian #1 or #2 went anything like today. I stammered, I got stuck, I butchered grammatical gender and case left and right and I knew it, I reached for words and found the wrong ones, or none at all. But through some combination of pride mellowing with age, and getting comfortable with my own failure, and talking about it in public, today went fine. I can laugh and shrug and ask for a word or phrase when I come up empty and keep going. (Re)learning a language is failure upon failure upon failure until the failure is sprinkled with success, and the successes eventually multiply. I have a lot more failing ahead of me this quarter.